Ultimate Fishkeeping Guide

- Choosing the Right Aquarium

- Choosing the Right Equipment

- Selecting the Equipment for Your Aquarium

- Setting Up Your Aquarium

- What To Expect in the First 60 Days

- Water Quality Basics

-

Water Chemistry

- How To Safely Raise pH:pH, Alkalinity, General Hardness

- Practical Fish Care Tips

- Buying New Fish

PART 1 - GETTING STARTED

Choosing the Right Aquarium

Choosing the right sized aquarium will depend on the amount of space you have, the kind of fish you want to keep and your budget.

There is a natural tendency to want to start small, especially when kids are involved. For one thing, smaller aquariums cost less, plus it is easier to find a place to put them. It is natural to feel that a smaller tank will be easier and less complicated to take care of, but actually the opposite is true. Larger aquariums are more stable and more forgiving of beginner mistakes. When things go wrong – as sometimes happens in the beginning – they tend to do so quickly and often with disastrous results in a smaller aquarium. That does not mean you should start your youngster out with a 55-gallon setup (although they probably would not object to the idea), it just means that unless you are planning to have a Betta and nothing more, a 10 or 20-gallon tank is a better choice than a tiny desktop aquarium. Also, if your budget and available space allow you to go larger, bigger is always better!

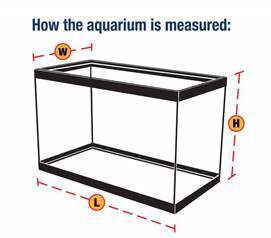

Aquarium dimension is important, too. Wider aquariums provide more surface area for gas exchange and more room for active fish to swim. They also offer territorial fish such as cichlids and freshwater sharks more places to set up and defend a home. Tall, narrow aquariums fit into tight spaces better, but they hold fewer fish per gallon and are best suited for less active fish such as angelfish and gouramis.

Glass vs Acrylic Aquariums

Another consideration is whether to go with a glass or acrylic aquarium; each has pros and cons. Glass tanks do not warp or scratch easily, they are less expensive and do not discolor over time. They are, however, more vulnerable to breakage. Acrylic tanks are lighter and although more expensive, are less vulnerable to breakage. When choosing a stand, the entire bottom of an acrylic or frameless glass tank must be supported, not just the edges as with a framed glass aquarium.

Where To Place Your Aquarium

- Place your new aquarium where you spend the most time so you can enjoy it! Make sure there is an electrical outlet close by.

- Avoid windows that receive direct sunlight, as this can affect water temperature and may contribute to excessive algae growth.

- In colder climates, avoid exterior walls and entry doors where winter drafts could cause a drop in water temperature.

- Avoid high traffic areas where your aquarium might get bumped.

- Do not place your aquarium on an uneven surface, near a fireplace or heating/air conditioning vent, or above electronic devices, books and other objects that could be damaged by water.

Choosing the Right Equipment

If this is your first aquarium, or it has been a few years since you set one up, boxed aquarium kits are a great way to get started as they eliminate having to figure out all the necessary equipment you will need, what size filter and heater to choose, etc. Most boxed starter kits include the tank, cover and light, filter, heater, thermometer, food and water conditioner samples, a net and setup guide, all at significant savings compared to buying each item separately. Aqueon offers a wide range of rectangular, hexagonal, bowfront and specialty aquarium kits from in sizes from 10 to 55 gallons.

For aquariums larger than 55 gallons, you'll need to assemble the equipment item by item. Here is a list of things you will need to complete your setup:

- Stand – An aquarium filled with water, gravel and decorations weighs approximately 10 lbs. per gallon. Sturdy household furniture can be suitable for aquariums of 5 gallons and smaller, however, for anything larger, an aquarium stand manufactured for the size tank you are purchasing is your best option because they are specifically designed to be strong enough to support your aquarium!

- Full Hood or Glass Cover & Light – A secure cover prevents fish from jumping out, keeps dust and foreign objects out of your aquarium and reduces evaporation. Fish should have a consistent day/night cycle and live plants need strong, high-quality light for proper growth. You have your choice between a full hood or a glass top with separate light fixture.

- Filter – A filter is the single most important piece of equipment for a successful aquarium. Unlike most other animals, fish live in the same environment they release waste into and it is essential to your fishes' health that this waste be processed quickly and efficiently. You can choose from internal, hang-on the back and canister filters to fit a wide range of aquarium sizes. Many experienced aquarists will fit their aquariums with slightly oversized filters or multiple filters in the case of larger aquariums to help keep them clean and clear.

- Heater – Warm water and stable temperatures are essential to keeping tropical fish healthy and free of disease. Sudden temperature changes stress fish and can trigger parasite outbreaks such as ick. Choosing the right heater for your aquarium depends on aquarium size, desired temperature and the minimum temperature of the room in which the aquarium is located. Multiple heaters are suggested for aquariums 100 gallons or larger. Options include Flat and Mini heaters for aquariums 10 gallons and smaller, as well as Preset, Submersible and Pro heaters for larger aquariums. Refer to the Aqueon heater guide below for the right sized heater for your aquarium.

- Thermometer – While many aquarium heaters have setting control dials, the actual water temperature may vary depending on water circulation and the location of the aquarium. An aquarium thermometer lets you know the exact water temperature. If using a stick-on thermometer, place it on the outside of the aquarium, above the gravel line, as far away from the heater as possible. Install the thermometer where you can easily read it and where it will not be affected by sunlight.

- Water Conditioner – Most municipal tap water contains chlorine or chloramine, and private well water may contain heavy metals, all of which are harmful to fish and other aquatic organisms. Use Aqueon Water Conditioner to neutralize these contaminants when filling an aquarium for the first time and before adding replacement water to the aquarium during a water change.

- Aerator – While an air pump is not a necessity, aeration does help maintain the dissolved oxygen level in your aquarium and aids in biological filtration. Air diffusers can be incorporated into decorations to enhance the aesthetics of your aquarium as well. A check valve should always be installed to prevent backflow when the air pump is unplugged or in the event of a power outage. Aqueon QuietFlow Air Pumps are available in 5 sizes and feature built-in check valves.

- Substrate – In addition to enhancing the aesthetics of your aquarium, a substrate gives beneficial bacteria a place to live. These micro-organisms help filter the water and provide biological balance to the aquarium. Use fine gravel for planted aquariums, medium grade in most community aquariums and coarse gravel for fish that dig a lot, like large goldfish and cichlids. Darker gravel accents the colors of your fish and conceals dirt better than lighter colored gravel. Rinse all gravel in plain water before placing in your aquarium.

- Decorations – Fish need structure to feel safe and secure, and to avoid being harassed by aggressive tank mates. Live or artificial plants, rockwork, driftwood and statuary (castles, sunken ships, figures) serve this purpose and give you an opportunity to personalize your aquarium and turn it into living art. Place taller plants and décor items near the back of the aquarium to provide backdrop and hide filter tubes, heaters and cords, with progressively shorter decorations towards the front.

- Background Material – In addition to providing visual depth and enhancing the overall look of an aquarium, a background also hides cords, hoses and other equipment. Background material should be installed on the outside of the aquarium before placing the aquarium on the stand and filling it with water.

- Test Kits – A test kit is recommended especially when starting a new aquarium. Toxic ammonia and nitrite levels can rise quickly in new aquariums and knowing your water parameters will help avoid problems and keep your fish happy and healthy!

Selecting the Equipment for Your Aquarium

Filtration

Fish release waste into the same environment they eat, breathe and live in, making an efficient filtration system critical to their long-term health and well-being. Choosing the best filter for your aquarium will depend on aquarium size, the types of fish you keep, your feeding habits, maintenance practices and to some extent your personal preferences.

Most filters on the market are rated for specific aquarium sizes, however, the bio-load in your aquarium is just as important if not more so. Simply stated, this refers to the number and size of fish and the amount of food being fed each day. For example, a 55-gallon aquarium with one or two large predatory fish may require a larger filter than the same sized aquarium with dozens of small schooling fish because predatory fish produce larger amounts of waste. Fish that are fed three times a day create more waste – or a higher bio-load – than fish that are fed once a day. For best performance, always choose a filter rated for a slightly larger aquarium than you have. For aquariums 100 gallons or larger, multiple filters may be required due to the long length of these size aquariums.

Stages of Filtration

There are three stages of filtration: mechanical, chemical and biological. Most aquarium filters perform all three but are sometimes better at one or two at the expense of the others.

Mechanical: The removal of solid waste, organic debris and other particulate matter by trapping it on fibrous or sponge material and then rinsing or replacing the media. This is typically the first stage of filtration, although ultra-fine media for “water polishing” is often placed at or near the end of the flow path in canister filters. The density of the material will determine what size particles are filtered out and the resulting water clarity. Finer media provides clearer water, but usually needs to be cleaned or replaced more often.

Chemical: The adsorption of dissolved pollutants using granular materials such as carbon, ion exchange resins, zeolite and other media. Carbon also removes the yellow or greenish tint common in mature aquariums. Specially treated pads that can be cut to size are also available and provide both mechanical and chemical filtration. Chemical filtration is typically the second or third stage in the filtration process but can vary depending on personal preferences and philosophies. This media must be replaced when exhausted or saturated.

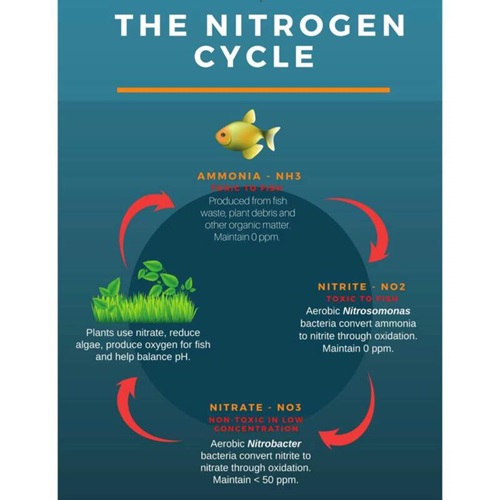

Biological: The conversion of toxic ammonia to nitrite, and then nitrite to nitrate through oxidation by nitrifying bacteria, often known as the Nitrogen Cycle or Biological Filtration. These bacteria grow on permanent media intended as the “home” for beneficial bacteria to live on. This media is not intended to be changed or replaced. Biological media can be composed of ceramic, sintered glass, plastics or even sponge. The best bio-media have very high surface area for maximum bacterial growth. Biological Filter media is generally the last stage of filtration allowing the beneficial bacteria to have the cleanest water possible.

Filter Types

|

External Power FiltersAlso known as hang-on-back (HOB) or simply hang-on filters, these are the most popular filters for small to mid-size freshwater aquariums because of their reliable performance and convenient maintenance. As their name suggests, they hang on the back of the aquarium and water is drawn or pushed into the filter chamber where it passes first through a replaceable carbon filled fiber cartridge and then some type of permanent biological media before returning to the aquarium. The discharged water agitates the surface, thus oxygenating the water and provides circulation within the aquarium. Some HOB filters can be manually loaded with individual media for more specialized use. Cartridges should be rinsed as needed and changed monthly. Most hang-on filters must be primed by filling them with water before plugging them in, however, Aqueon® QuietFlow LED PRO and the Coralife® Marine Filter with Protein Skimmer are all self-priming. QuietFlow LED PRO filters also feature an LED filter cartridge change indicator, which turns on when water flow indicates the cartridge needs replacing or rinsing, and Specialty Filter Pads provide additional chemical filtration. |

Canister FiltersCompared to HOB’s, canister filters hold more media and offer the aquarist unlimited flexibility in terms of media options. They are typically used on mid-size to larger aquariums in both freshwater and saltwater applications. Canister filters are positioned below the aquarium, usually inside the cabinet stand. Water is drawn into the filter through an intake tube, passes through the media and is then pumped back to the aquarium via a return tube. A spray bar or directional jet is used to agitate the surface and provide current in the aquarium. Canister filters function best as mechanical filters and are ideal for large aquariums, those with fish that create a lot of waste or fish that like strong current. Aqueon® QuietFlow® Canister Filters come in 3 sizes and feature a unique water return option, the Water Polishing Unit which serves as the final stage of filtration. |

|

|

Internal Power FiltersThese filters are placed inside the aquarium and are driven by an integrated pump. Open style filters attach to the aquarium glass by suction cups or hang on the rim using clips. Water is filtered through a standard HOB filter cartridge. Closed style internal filters pass water through mechanical, chemical and biological media chambers before directing it back into the aquarium through a controllable directional nozzle. Aqueon QuietFlow E (open style) and QuietFlow Internal (closed style) Power Filters are available in multiple sizes. QuietFlow Internal Power Filters can be installed vertically or horizontally and have adjustable flow rates and directional control, making them ideal for paludarium or riparium use. |

Sump or Wet/Dry FiltersThese filters were initially developed for the marine hobby, but can be used in freshwater systems, as well. Placed below the aquarium, water is gravity fed from the aquarium down to mechanical filtration medias, such as a fiber sock or other filter pad material and into the first chamber of the sump. From there, water is distributed over biological media where carbon dioxide is released, and the water is oxygenated. Additional chambers can be used for heaters, chemical filtration media, protein skimmers (used in marine aquariums only) and/or other purposes, depending on the needs of the aquarium. After flowing through all the chambers, water is pumped back to the aquarium. There are many different variations of sump filtration systems, but the basic function is the same no matter the design. |

|

|

|

Sponge FiltersSponge filters are placed on the bottom of the aquarium. Using an air pump, water is drawn into the sponge and ejected through an exhaust tube. Some mechanical filtration occurs, however, their main function is as a biological filter. Due to the high surface area in the sponge, they filter fairly large volumes of water relative to their physical size. While not often used in display aquariums, many breeders use them in nursery tanks because they will not trap baby fish and they support important micro-organisms that serve as first food for newly hatched fry. |

Lighting

Choosing the right light is one of the most important aspects of an aquarium. It can also be one of the most confusing, especially for beginner aquarists. Choosing the best light fixture for your aquarium depends on the needs of the animals and plants you’ll be keeping, the size and dimensions of your aquarium and your budget.

Fish and Plant Needs

One of the most important reasons to have a light on your aquarium is to enjoy the beauty of the fish, plants and decorations. In addition, the fish need to see so they can get around, find food and interact with each other. But there are other considerations; live plants and certain species of fish have specific light needs. Some fish inhabit open water in rivers, streams and lakes, where the light is bright most of the day. Others prefer dimmer habitats among fallen logs or under overhanging vegetation. The same applies to plants; some grow in shallow or open water, where the light is bright and constant throughout the day. Others are found in deeper water or in the shadow of taller plants or overhanging shrubs and trees. It’s important to choose a light that is appropriate for the types of fish and plants you keep.

Light Intensity and Spectrum

Not all light is created equal. Intensity refers to how strong or “bright” a light is. Spectrum is a way of describing the mixture of different colors – or wavelengths – a light produces. Light spectrum is often given a Kelvin rating or "K rating". Light sources that give off a yellowish or warm effect have a low Kelvin rating, while those that produce a crisp bluish-white or cool light have a high Kelvin rating. Most freshwater aquarium lights are rated between 5,500 and 8,000 Kelvin.

Intensity and spectrum are less important in aquariums or with artificial plants, although some lights enhance natural colors better than others. A light that’s too intense may promote algae, especially in non-planted tanks and may make more timid fish hide in the shadows. Where live plants are concerned, proper intensity and spectrum can make the difference between success and failure. Water depth is a factor as well. Certain wavelengths, especially blue, penetrate deeper into water than others, and this can be critical to live plants. Let your local dealer know your tank’s height and the types of plants you want to keep when getting advice on the best light fixture for your aquarium.

PRO Tip: Read more on how to keep live plants in your aquarium here.

Type of Light Fixtures

There are several types of aquarium lights, allowing aquarists to choose one that best suits their needs and those of their aquarium inhabitants. Aqueon® and Coralife® offer a wide range of full hoods, strip lights and clip-on lights. Here are some common choices for freshwater aquariums:

Standard FluorescentFor years this has been the most common form of aquarium lighting and it continues to be popular today. Affordable pricing and a selection of bulbs for different applications make fluorescent lights a great choice for many aquarists. Aqueon offers strip lights and full hoods as well as a selection of bulbs for rectangular, hexagon and bowfront aquariums. Bulbs dim over time and should be replaced every 10 to 12 months. |

|

LED

Rapidly becoming the most popular type of aquarium lighting, these energy-efficient lights offer features that are not available in other aquarium lights. Aqueon LED lights are available for aquariums of almost any size. They use far less energy than other lights, do not heat the water and the LEDs last several years without losing intensity. OptiBright lights feature higher intensity, programmable timers, output (intensity) and spectrum controls, nighttime moonlights, adjustable sunrise/sunset and moonrise/moonset timers and different color options!

|

|

|

|

| Aqueon Planted Aquarium Clip-On LED | Aqueon OptiBright MAX LED Light | Aqueon Modular LED Aquarium Lights | Aqueon LED Deluxe Full Hoods |

|

|

|

|

Day/Night Cycle

It is important for all living things to have a regular day/night cycle for optimum health and well-being. In the tropics, where most aquarium fish, invertebrates and plants come from, there are 12 hours of light (known as the photoperiod) and 12 hours of darkness every day of the year. Planted aquariums do best with 12 hours of light, while those without live plants will have less algae with a photoperiod of approximately 8 to 10 hours. Use a timer on your aquarium light to create a consistent day/night cycle. To enjoy your aquarium during evening hours, place it away from windows and set the timer accordingly.

Algae & Light

A commonly held belief in aquarium keeping is that too much light causes excessive algae growth. Algae are nature’s way of purifying water and are a natural part of any aquarium. The truth is that nuisance algae outbreaks are more often caused by nutrient build-up rather than lighting issues. Planted aquarium owners rarely need to clean algae even though they use high output lighting because nutrients are quickly utilized by the plants, thus starving any algae. The trick to preventing algae growth is to manage nutrients with regular water changes, filter media and not overfeeding your fish, along with providing the right amount of light.

Choosing the right light for your aquarium enhances its natural beauty and ensures the long-term health of your fish, plants and invertebrate life!

Heating

Many aquarium fish are from tropical climates which means heat is needed to recreate these warm waters. Some heaters produce a constant supply of heat and others have an internal thermostat that regulates when the heater turns on and off. The ability to adjust the temperature is a feature of some heaters but others are preset to a tropical temperature, commonly 78⁰F, for a “set it and forget it” simplicity. Selecting the proper size heater is important; too small and the heater cannot effectively warm the aquarium, too large and the temperature can fluctuate too quickly. All Aqueon Heaters come with a Safety Shutoff feature that will turn the heater off if accidentally left plugged in when removed from the water. This prevents the heater from overheating causing damage. See the Heater Selection Chart for a great comparison visual to see the differences between the heater families.

Types of Heaters

Flat HeatersThis family of heaters produces a constant supply of heat so there is no need to guess what temperature to set for the aquarium. These are compact in design and can easily be hidden behind decorations and plants. It is important to pay attention to the aquarium size recommendations for these heaters. Because of the constant heating, an oversized heater can warm the water too much, stressing the fish. These heaters come in multiple sizes for aquariums 1 gallon to 6 gallons.  Flat Heaters Flat Heaters

|

|

|

|

|

Mini HeaterThis compact heater is preset to 78⁰F and ideal for smaller aquariums up to 2.5 gallons to 5 gallons. In addition to the Safety Shutoff, the heater is made of a shatterproof and nearly indestructible construction. Being completely submersible and a compact design, it can be easily concealed in the aquarium to not detract from the aquarium’s aesthetic. |

Preset HeatersSometimes simplicity is key. This line of heaters is preset to 78⁰F requiring no adjustment for the perfect temperature. They come in several sizes to fit 10-gallon aquariums all the way up to 75-gallons. This heater is made of a shatter resistant quartz glass and an LED Light that indicates when the heater is actively heating.  Preset Heaters Preset Heaters

|

|

|

|

|

|

Submersible Aquarium HeatersHaving the ability to select a specific temperature for your aquarium can be important for species like Discus that like warmer waters. This heater line has a temperature adjustment knob at the top to select the desired temperature and an LED light that indicates when the heater is actively heating. It has a shatter resistant glass construction, but more aggressive or large fish can still break the glass. This is an important thing to think about when choosing a heater. Be sure to attach the suction cups above the coil heating elements to prevent them from overheating.  Submersible Heaters Submersible Heaters

|

Pro HeatersThe high-end shatterproof construction and adjustable dial at the top makes this a premium heater line. The LED indicator light, located in the adjustment dial, illuminates when the heater is actively heating. The dark design makes the heater blend it behind plants and decorations. The heater is fully submersible so it can be positioned vertically (with the dial at the top) or horizontally in the aquarium. The stronger construction is ideal for larger fish that can be tough on items in the aquarium.  Pro Heaters Pro Heaters

|

|

AQUEON HEATER GUIDE

|

To Increase Above Room Temperature: |

|||

|

Aquarium Size |

5° F |

10° F |

15° F |

|

5 Gallon |

50 watt |

50 watt |

50 watt |

|

10 Gallon |

50 watt |

50 watt |

50 watt |

|

20 Gallon |

50 watt |

100 watt |

100 watt |

|

30 Gallon |

100 watt |

100 watt |

150 watt |

|

55 Gallon |

150 watt |

150 watt |

200 watt |

|

75 Gallon |

200 watt |

200 watt |

300 watt |

|

100 Gallon |

300 watt |

300 watt |

300 watt |

|

120/125 Gallon |

2 x 200 watt |

2 x 200 watt |

2 x 200 watt |

|

150 – 210 Gallon |

2 x 300 watt |

2 x 300 watt |

2 x 300 watt |

Setting Up Your Aquarium

Be sure to read all instructions before assembling and installing equipment and always incorporate a drip loop on any electrical items.

- Install background material by laying the aquarium face down on a carpeted or protected surface and attach it using tape or hook and loop strips such as Velcro.

- Position the aquarium and stand far enough from the wall to accommodate filters, hoses and cords. Make sure the stand is level and does not rock or wobble. Use wood shims to level and stabilize the stand if necessary.

- Rinse gravel with tap water using a colander, wire strainer or fish net. Do not use bleach, soap or use other cleaning products.

- Assemble and install the filter in the aquarium. Position the outflow to provide circulation throughout the aquarium. Do not plug it in yet.

- If your heater has a control dial, set it to the desired temperature (75° - 80° F for tropical fish) and install it in the aquarium. Position it near the filter inlet or outflow or an air diffuser to ensure even heat distribution throughout the aquarium. Submersible heaters can be installed horizontally for more efficient heat distribution. Do not plug the heater in yet.

- Install a thermometer at the opposite end of the aquarium from the heater.

- Fill the aquarium about halfway with room temperature water that has been treated with water conditioner. Place a plate or saucer on the bottom to avoid stirring the gravel as the water enters.

- Install artificial plants, rockwork, driftwood and other decorations at this time. Live plants and fish should not be added until the aquarium has been running for at least 48 hours.

-

Once you have added decorations, fill the aquarium to 1” below the

rim. Prime the filter (if necessary) and plug it in using a drip loop. A

drip loop is when you allow the cord to drop below the outlet before it

rises up to plug in.

Pro Tip: Aqueon QuietFlow hang-on filters do not need to primed, they are self-priming; simply plug it in! - If using an aerator, plug it in now. Keep air diffusers and bubble wands away from filter intake tubes, as they may cause the filter to stop if air is drawn in.

- After 30 minutes, plug the heater in.

- Place the cover and light on the aquarium and plug the light in. Place your aquarium light on a timer to provide a consistent day/night cycle which fish, live plants and other aquatic organisms need to thrive.

Congratulations! You’ve just set up your aquarium! Now sit back and relax while you consider what kinds of fish and other living creatures to put in it.

How To Set Up A Large Aquarium

What To Expect in the First 60 Days

Having a new fish tank is exciting stuff! In the first two months after setting up your new aquarium, you are likely to see it go through a lot of changes; most are natural, but some changes may be signs of trouble. It is important to know which is which. It is going to take time for your new environment to find balance, but by knowing what to expect in the first 60 days, you will be able to help it along.

The First 5 Days After Setup:

- You are going to be excited and anxious to fill your new aquarium with fish. Be patient! Let your aquarium “settle” for at least 48 hours before buying your first fish or live plants. This will give you time to make sure the temperature is set correctly and to make adjustments to decorations, etc.

- Unless you have already decided on what fish you want to put in your new aquarium, check the list of suggested beginner fish below or consult your local aquatic expert.

- Resist the temptation to add too many fish at once! Your filter will not be able to process a lot of waste at first and this could cause harmful ammonia and nitrite to rise to unsafe levels.

- Occasionally the water in a new aquarium will turn cloudy after you introduce the first fish. This is caused by a bacterial “bloom” and will usually clear on its own in a few days. These blooms are usually harmless to fish, but it is a good idea to test for ammonia and nitrite to make sure they remain at zero. Resist the desire to do a water change if ammonia and nitrite are not detected! Water changes typically prolong the bloom by providing them with nutrients, and large water exchanges can stress your fish. Adding Aqueon PURE can help speed up the process by adding the bacteria directly to the aquarium in large volumes.

SUGGESTED STARTER AQUARIUM FISH:

|

|

Harlequin Rasboras |

|

White Cloud Minnows |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 to 15 Days After Setup:

- Your new fish may hide at first. They are likely stressed from being moved from the store and placed in a new environment. Make sure they have plenty of cover and hiding places to make them feel safe and secure. For especially shy fish, leave the aquarium light off for a few days (if you do not have live plants) until they start to come out and enjoy their new home.

- Feed sparingly! A good rule of thumb is to feed only what the fish can consume in 2 minutes or less. Feed once daily for now, until your tank goes through its first cycle. Indications of overfeeding include food lying on the bottom after 5 minutes, cloudy water, foaming at the surface or an odor when you open the aquarium lid.

- Test your aquarium water for ammonia and nitrite. Even if you do everything right, these levels may begin to rise until the nitrifying bacteria in your filter catch up. Use Aqueon Ammonia Neutralizer, water changes or chemical filtration media to prevent them from reaching dangerous levels. If in doubt, consult your local aquatic expert for assistance. The team at Aqueon is also available to help should you have questions during the process.

- Once ammonia and nitrite levels return to zero, your aquarium has completed its first cycle. You may now introduce additional fish.

15 to 30 Days After Setup:

- As ammonia is converted to nitrite and then nitrate, algae may begin to grow on the glass and other objects in the aquarium. This is normal and is an indication that the Nitrogen Cycle is becoming established. Remove algae from the glass using a scrub pad or algae scraper. Never use a scrubber that has been used with soap or chemicals!

- As long as ammonia and nitrite levels are at zero, you can continue adding fish to the aquarium during this period. If algae has started to appear, introduce algae eating fish such as plecostomus, otocinclus, snails and other scavengers. If you do not want to add more fish to your aquarium, try adding Aqueon Algae Remover to help keep algal blooms under control.

- Always test water before purchasing new fish, and only buy a few fish at a time. Wait at least a week between new fish additions. Consider buying a plant or decoration with each fish purchase to give newcomers to the aquarium their own place to call home.

- Occasionally, fish that have become established in the aquarium will act aggressively towards new fish because they consider the newcomers intruders to their “territory”. This is especially true among cichlids. Rearranging the aquarium décor and adding new decorations will often calm this behavior by eliminating territorial boundaries.

-

Perform a 25% water change after 15 days. Do not vacuum the gravel yet, as

you may disrupt the good bacteria that are just starting to colonize your

aquarium. Remember to treat tap water with Aqueon

Water Conditioner

before adding it to your aquarium.

Pro Tip: There are different philosophies on how much and how often to change water, but 10% to 25% every 1 to 2 weeks is a good rule of thumb. Small, frequent water changes are best. It’s important to build a habit of water changes. - Check the cartridge(s) in hang-on and internal filters, or mechanical filter media in canister filters and rinse solid waste off as needed. If the cartridge or fiber pads seem especially dirty, you might be overfeeding! Do not disturb biological media at this time.

30 to 60 Days After Set Up:

- Begin feeding twice daily, as long as ammonia and nitrite levels remain at zero. Once ammonia and nitrite are zero the Nitrogen Cycle is complete (read more about Nitrogen Cycle in the next section) Feed only what your fish can consume in 2 minutes or less. It is okay to skip a feeding every few days. In fact, this is actually beneficial as it allows fish to clear their digestive systems.

- Change the cartridge(s) on hang-on and internal filters, or mechanical and chemical media (carbon, ammo-chips, etc) in canister filters after the first 30 days and then once a month thereafter.

- Observe your fish closely, especially at feeding time. Get to know their behavior as they interact with each other and swim around the aquarium. Watch for rapid breathing, gasping at the surface, clamped fins, white spots on fins or bodies, scratching against objects, unusual behavior, or external markings that were not there before. Consult your local aquatic expert if you have questions or concerns.

Congratulations! You have now gone past the first 60 days of owning an aquarium, we hope you continue with this calming and enjoyable hobby for many years to come. Now it is time to set up your next aquarium!

PART 2 - CARE & MAINTENANCE

Water Quality Basics

The Nitrogen Cycle

The Nitrogen Cycle is how waste is processed in an aquarium. Fish release waste in the form of ammonia (NH3), which is toxic to aquatic organisms. Nitrifying bacteria living in the filter, gravel bed, and on solid objects in the aquarium convert ammonia to nitrite (NO2), which is also toxic. Nitrite is then converted to nitrate (NO3) by a different set of nitrifying bacteria. Nitrates are not toxic to fish per se, however, long term exposure to high levels can stress them, stunt their growth, damage organs and make them more susceptible to disease. Nitrates are used by aquatic plants, but if allowed to accumulate nitrates, contribute to unsightly algae growth. Additional sources of biological waste include uneaten food and dead plant material.

Ammonia (NH3 and NH4+) – the primary component of fish waste. Ammonia is harmful to fish and tends to rise in newly established aquaria due to a lack of nitrifying bacteria, adding too many fish at once, overfeeding or a combination of these factors. It can also rise in heavily populated tanks due to generous feeding and/or insufficient filtration. In water, ammonia exists in two forms: free ammonia (NH3) and ammonium ion (NH4+). Aquarium water test kits usually measure NH3 and NH4+ combined. The only safe level of Ammonia in an aquarium is zero.

Ammonia is more toxic at higher temperatures and pH levels above 7.0

Ammonia is less harmful at lower temperatures and pH levels below 7.0

Nitrite (NO2) – nitrifying bacteria living in the filter and aquarium convert ammonia to nitrite (NO2). A rise in nitrite usually follows an ammonia spike. Nitrite prevents oxygen exchange to fishes’ bloodstream, and high levels can cause them to suffocate. Fish that are experiencing nitrite toxicity will often breathe rapidly and gasp at the surface (although there are other reasons they do this), and their gill filaments will turn from bright red to dull brown or grey in color. The only safe nitrite level is zero.

Nitrate (NO3) – nitrite is converted to nitrate (NO3) by nitrifying bacteria. While nitrate is far less toxic to fish and other aquatic organisms than ammonia and nitrite, it can stunt your fish’s growth and long-term exposure to high levels stresses them and compromises their immune systems. Nitrate is also a major contributor to algae growth. Some tap water sources are high in nitrate, so it’s a good idea to test your tap water before using it. Nitrate toxicity to fish varies depending on species, age and overall health, but levels above 50 ppm are undesirable in freshwater aquaria. Regular partial water changes, proper filtration, sensible stocking and feeding habits as well as the use of live plants will help keep nitrates in check.

Water Chemistry

pH – pH is the measure of whether water is acidic (pH 1 to 6.9), neutral (pH 7.0) or basic (pH 7.1 to 14). Most freshwater aquarium tropical fish do best at a pH of 6.8 to 7.6, although certain species may require higher or lower levels. There is a natural tendency for pH to gradually drop in an aging aquarium as organic waste accumulates and mineral buffers are depleted. Left unchecked, pH can drop low enough to stress our aquatic pets. To avoid this, regular partial water exchanges should be done to remove pollutants and replenish minerals that naturally buffer pH and keep it stable.

Minor changes in pH also occur between day and night, especially in well-planted tanks. Plants produce oxygen by day, which contributes to a rise in pH, and they give off carbon dioxide at night, which lowers pH. These fluctuations are more pronounced in tanks that have low buffering capacity or use supplemental CO2.

pH is also important when cycling a new aquarium, when ammonia can build up due to a lack of nitrifying bacteria to process it. As mentioned above, ammonia is more toxic as pH rises above 7.0, and is less toxic at pH below 7.0. When cycling a new aquarium, test pH, ammonia and nitrite regularly to avoid stressing your fish. Unless you are trying to breed sensitive or wild caught fish from environments with extremely low or high pH, it is best not to try to change it. Most fish will adapt as long as Nitrogen Cycle is established and pH is stable.

But what if your tap water pH is unusually high or low? Or perhaps it’s within range, but you want to keep or even breed wild caught fish that come from extreme habitats? Aquarium shops sell products that modify pH, but these should be avoided altogether or used with extreme care by experienced aquarists to avoid sudden or drastic pH shifts. Some products, especially liquid pH adjusters, often have only temporary effects and pH soon shifts back to its original value, making it necessary to keep adding more. The resulting pH roller coaster this creates is very stressful to aquatic creatures.

If you do decide to adjust the pH in your aquarium, it is best to do it BEFORE introducing fish or other livestock and test regularly to make sure it remains stable. If you already have fish or other creatures in your aquarium, never make sudden or drastic changes to pH or any other water parameters. Below are some natural methods for adjusting pH that are longer lasting and more stable over time.

How To Safely Lower pH:

- Use reverse osmosis (RO) or deionized (DI) water to create the desired pH and provide buffering. Always prepare water and test pH before adding it to your aquarium.

- Decorate your aquarium with natural driftwood. Tannins released by driftwood can help lower pH, but keep in mind that it takes a fair amount of driftwood to have the desired effect. One or two small pieces will not do much, especially in a large aquarium or one with strong buffering capacity.

- Add peat moss or peat pellets to your filter. Like driftwood, peat moss contains tannins that lower pH. Use a mesh media bag to keep it contained and use only peat products designed for aquariums. Replenish as needed to maintain the desired pH.

How To Safely Raise pH:

- Use reverse osmosis (RO) or deionized (DI) water to create the desired pH and buffering. Always prepare water and test pH before adding it to your aquarium.

- Use crushed coral or dolomite gravel for substrate. These calcium carbonate-based gravels slowly dissolve over time, raising and buffering pH.

- Decorate your aquarium with limestone or coral rock. As with driftwood for lowering pH, use a healthy amount of calcium carbonate rock to create the desired effect.

- Fill a mesh media bag with crushed coral or dolomite gravel and place it in your filter.

Alkalinity (KH) – Alkalinity is the measure of carbonates and bicarbonates in water and represents the ability to resist changes in pH. Carbonates help stabilize pH in the aquarium and are replenished through regular partial water exchanges or the addition of buffers. Most captive-bred fish will adapt to your aquarium’s alkalinity, so it is usually not necessary to adjust it. Unless you are keeping wild caught fish that come from extremes in pH or hardness, it’s best to acclimate new fish to your tank’s conditions.

General Hardness (GH) – General Hardness is a measure of calcium, magnesium and other ions in water, sometimes referred to as Total Hardness. Most freshwater fish adapt to a wide range of general hardness, and it is best to adjust them to your local water. Unless you are trying to keep or breed fish from areas of the world with extremes in water hardness, do not try to manipulate the pH or hardness level in your aquarium with additives. If your tap water is excessively hard or soft, the use of reverse osmosis or deionized water with Aqueon Water Renewal added is a more natural and stable way to adjust GH.

Practical Fish Care Tips

Our fish depend on us to create the best environment and see to their every need. Here are some ways we can accomplish this:

Habitat

Most aquarium fish need structure in their environment to feel safe, establish territory, breed or seek refuge. In a well-decorated aquarium, fish tend to stay out in the open and are less stressed. Territorial and semi-aggressive fish tend to quarrel less when there is ample cover. Decorating is also one of the most rewarding aspects of owning an aquarium. It allows you to personalize your aquarium, exercise your creative skills and turn that glass box into living art!

When decorating your aquarium, always take the needs of your fish into consideration. For example, schooling fish such as tetras, barbs, danios and rasboras enjoy swimming among plants (live or artificial), and choosing darker colored plants helps accent their bright colors. Place taller plants towards the back of the aquarium to create a backdrop and hide heaters, cords and filter tubes, with progressively shorter plants towards the front. For surface-oriented fish like gouramis, hatchetfish and livebearers, use plants that are taller than the aquarium to create overhangs. Floating plants such as duckweed, hornwort and Salvinia create the same effect and are easy to grow.

Fish that like to “den”, such as redtails, rainbow sharks, certain types of cichlids, loaches, catfish, and certain types of plecostomus find refuge in hollow logs, caves and ornaments like sunken ships. They will often patrol the entrances to their lairs and ward off any fish that come too close. In aquariums with discus or angelfish, decorate with pieces of driftwood angled from the surface down to the bottom to simulate the fallen trees and branches in their natural environment. For Rift Lake cichlids, use plenty of rockwork to simulate the bolder fields found in their natural habitat.

When introducing new additions to an aquarium with territorial fish such as cichlids, it’s a good idea to rearrange existing décor to eliminate old territorial boundaries and add one or two new decorations to create additional habitat for the newcomers.

Feeding

Fish in nature spend much of their day either eating or trying to avoid being eaten. Some fish are omnivorous, meaning they eat a mix of protein and vegetation of food. Others are herbivorous, feeding mostly on plant matter. Which leaves the carnivores, who feed on meaty foods such as insects, worms, crustaceans, amphibians, other fish and even small birds and mammals! Large predatory fish eat less frequently, while herbivores and omnivores graze throughout the day.

Knowing what kinds of things your fish eat in nature will help you choose the right food for them and gives some indication of how often they need to be fed. Most fish do best when fed once or twice daily. All food should be consumed in 2 minutes or less. Large predators do not catch food every day in nature, and do not need to be fed every day in the aquarium. Herbivores and fish that forage throughout the day should be fed small quantities of food two to three times daily. Aqueon offers a complete line of flake, pellet, tablet and dried whole foods to accommodate the nutritional needs of most ornamental fish.

Fish will normally find food whether it’s at the surface, in mid-water or on the bottom. However, presenting it in the way they normally feed is helpful, especially for new arrivals or finicky eaters. For example, feed bottom feeders sinking foods, and flake or floating pellets to surface and mid-water feeders. Sometimes more aggressive feeders may intimidate shy fish, preventing them from getting enough to eat. Try feeding boisterous fish first and once they are distracted, direct some additional food to sheltered areas where shy fish can eat in peace. Finally, many plecostomus, catfish and knifefish are nocturnal and stay hidden until the lights go out. While some may learn to eat during daylight hours, many will stay hidden and may not get enough to eat. Feed these fish after the aquarium light is turned off at night.

Water Exchanges

Regular partial water changes remove pollutants and growth inhibitors that accumulate over time and help stabilize pH and buffering capacity in your aquarium. They replenish trace elements and important minerals that are used by fish, invertebrates and plants, as well as the biological processes that maintain balance in your aquarium.

There are different philosophies regarding water changes in an aquarium, but the best practice is to do small partial water changes on a regular basis. The most successful aquarists perform a 10% to 25% water change on their aquariums every week. Changing more than 50% of the water at one time is not recommended. This helps remove unwanted waste while also replacing stale water with fresh and clean. Even though it may not look dirty, the waste can build up over time and is chemically altering the environment your fish live in. This waste remains in the water and does not evaporate out so simply topping off the aquarium is not preforming a “water exchange” or “water change”.

PRO Tip - Heavily stocked aquariums, those that house large messy fish or extremely sensitive fish, and aquariums that are fed generously will benefit from more frequent changes.

If your tap water has unusually high pH or alkalinity or is unsuitable for aquarium use due to high nitrates, phosphates or other problems, consider using a Reverse Osmosis (RO) or Deionized (DI) water. Add a trace element supplement to replace essential minerals and buffers that restore water to its natural state and promote optimum health, color and vigor in your fish and live plants.

3 tips to succeed

3 tips to succeed

Questions When Buying A New Fish

Buying new fish for your aquarium is exciting! Whether you’re new to the hobby or a seasoned veteran looking for something interesting to add to your aquarium, going to the fish store is just plain fun. There are so many fish to choose from you might have trouble deciding what to buy, and you could find yourself wanting them all! But before making any livestock purchase, there are some important questions you should ask to make sure you’re making the right decisions for yourself and the fish:

- How big will the fish get? Many of the fish you see in the store aren’t fully grown. Some may only get a little bigger, while others may double, triple or more in size. Always make sure the fish you intend to buy will fit comfortably in your aquarium when they reach adult size.

- What does the fish eat? While most tropical fish do just fine on a diet of flake, pellet or frozen foods, some species are specialized feeders that may require live food or customized feeding methods. Some fish may grow up to eat the rest of the fish in your tank, while others may be herbivores that will decimate a beautifully planted aquarium. Before purchasing any new aquarium fish, make sure you have the means and dedication to properly feed it and that it won’t devour the rest of your aquarium’s inhabitants or plants.

- Is the fish species peaceful or aggressive? If you have peaceful fish, you don’t want an aggressive fish that spends its day chasing everyone else around, stressing them. On the other hand, if you have rambunctious fish, you wouldn’t want to add a shy fish that will be constantly harassed and running for its life. While some fish may not kill their tankmates outright, being chased, nipped and kept from feeding will eventually take its toll on the victim, resulting in increased susceptibility to disease or even death.

- Is the fish territorial? There’s a difference between being aggressive and being territorial, although some fish can be both. Territorial fish will often tolerate other tank inhabitants as long as they have enough space and structure to define their territorial boundaries. They may chase other fish away if they come too close, but they will otherwise leave them alone. Territorial fish often do not tolerate other members of their species, so it’s best to just buy one.

- Will it get along with my fish? Keep a list of the fish you have in your aquarium. If you’ve forgotten or are not sure what kinds of fish you have, take pictures to show store staff so they can help you make the right choices. Just as people do, fish have personalities of their own and there is no guarantee that all fish will get along. Learn more about fish compatibility in our helpful article: Fish Compatibility: How to Build a Peaceful Community Fish Tank

- Does it need special water parameters or temperature? While most tropical fish sold today are raised in captivity and tolerate a certain range of water chemistry parameters, some are still collected in the wild and may need a specific pH, alkalinity or temperature to thrive. Always research the type of fish you intend to buy or ask if they need special conditions.

- How many fish should I buy? Some fish are solitary and as adults they do not tolerate others of their own kind or closely related species: betta fish, certain gouramis, redtail and rainbow sharks, and many cichlids are good examples. Schooling fish (tetras, barbs, danios, rasboras), on the other hand, do best in groups of 6 or more and may hide or become stressed if kept individually or in smaller groups. Livebearing fish (guppies, mollies, platies and swordtails) do best in a ratio of three females to one male as the males tend to be relentless in their efforts to mate.

- How long will the fish live? Small fish like tetras, barbs and danios should live at least 5 years, if not longer, while medium sized fish such as angelfish and goldfish often live 10 to 15 years. Larger cichlids, clown loaches, and many plecostomus and catfish species can live 20 years or more, while koi are known to live even longer. Plan accordingly.

- How long has the fish been in the store? Never buy a fish that has just arrived in the store. Shipping stress temporarily lowers a fish’s resistance and increases its susceptibility to disease. Moving it again without giving it a few days to stabilize will only compound the problem. This is especially true of wild caught or delicate species.

- What part of the aquarium will it occupy? Many fish spend their time at specific levels in the water column, and it’s important both visually and in terms of compatibility to have equal proportions of surface, mid-water and bottom dwellers. Crowding fish in any layer may result in conflict and stress to some of them.

- What type of habitat does it need? In nature, fish occupy specific habitats such as open water, plant beds, rock structure or fallen trees. Always research fish before you purchase them and make sure you have the proper habitat in your fish tank.

Asking key questions and making sure you have the right conditions for fish before purchasing them will ensure they live long and happy lives and result in many years of enjoyment with your aquarium.

Transport and Acclimation

Properly acclimating new fish purchases into your aquarium has a significant impact on their long-term health and well-being. Netting, bagging and transporting fish stresses them and to compound things, water quality and chemistry can vary between your local fish store and your aquarium. Precautions should be taken to ensure the transition is as stress free as possible. The greater the difference between store water and your aquarium, and the longer your fish are in transit, the more time and care you should exercise when acclimating them. In addition, some fish are more sensitive to changes and require more gradual acclimation.

Go straight home with new fish. In extremely cold or hot weather, transport fish in an insulated cooler or Styrofoam shipping container. Do not place fish in the trunk of your car. Finally, be sure to research the fish you are buying in advance to make sure you have the right conditions in your aquarium.

Drip Acclimation

Some fish are too large to acclimate while floating in an aquarium. Other fish are sensitive and require a more delicate process. In these instances, drip application is the best method. Airline tubing and a flow regulator are used to control the rate at which the water goes into the bucket. Watch the video to learn more.

Floating Acclimation

Acclimating fish to a new home is important for both the health of the fish and aquarium. Turning off the lights can help reduce stress in fish while they adjust to the temperature of the aquarium. A floatation ring is created by opening the bag and rolling it towards the outside to keep the bag afloat during the acclimation process. Watch the video to learn more.

Betta Acclimation

A common aquarium to set up is for Bettas. It is recommended to use the floating acclimation method. Be sure to discard any water from the bag and not add it to the aquarium. Watch the video to learn more.

Nutrition and Feeding

Often times, the first questions aquarists have after setting up their tanks have to do with feeding. What do I feed my fish, how much should I feed them, and how often? In nature, what fish eat depends on whether they’re herbivores (plant eaters), carnivores (meat eaters) or omnivores (both). How often and how much they eat depends on their dietary preferences, their appetite and availability of food.

Most aquarists keep a variety of species in their aquariums, so offering a combination of different foods is best. For example, livebearers are largely herbivores, while tetras are more carnivorous. If you keep both types of fish in your aquarium, as many aquarists do, alternate feedings of meat protein and plant-based foods to keep everyone happy and healthy. Variety is important regardless of what types of fish you keep, as even carnivores benefit from some plant matter in their diet, and vice versa.

The size of the food you feed should match the size of your fishes’ mouths. In other words, large predatory fish will usually show no interest in small flake crumbles, and small fish like Neon Tetras can’t fit large pellets into their mouths. Uneaten food will quickly pollute your aquarium.

How Much to Feed

It’s always best to underfeed, especially in new aquariums, as uneaten food can cloud your water and cause ammonia and nitrite levels to rise. A general rule of thumb is to feed only what your fish can consume in 2 to 3 minutes. When in doubt, start with a tiny quantity and observe how fast your fish consume it. If it is completely consumed in less than 2 minutes, give them a little more. It won’t take long to figure out how much food to give them at each feeding. Remove any food that remains after five minutes with a siphon hose or net.

Where Fish Feed

Another consideration is what part of the water column your fish feed in. Some species feed at the surface, some feed in mid-water and others are bottom feeders. Most fish will learn to take food wherever it’s available, but shy fish may wait until food drifts into their “safe zone”. These fish may need to be target fed, meaning directing food right to them. Flakes and some pellet foods typically linger at the surface for a minute or two before beginning a slow descent to the bottom, making them good choices for surface and mid-water feeders. Soaking dried foods or “swishing” them at the surface will help them drop faster for mid-water feeders. Most catfish, loaches and other bottom feeders do best on sinking tablets, wafers and pellet foods. When feeding frozen foods, dispense food a little at a time using a turkey baster or large syringe to make sure everyone gets some. Drop a little food at the surface for top feeders and gently squirt some lower into the water column for mid-water and bottom feeders.

How Often To Feed

For the most part, feeding your fish once or twice a day is sufficient. Some hobbyists even fast their fish one or two days a week to allow them to clear their digestive systems. Larger, more sedentary fish can go longer between meals than smaller, more active fish. Herbivores forage throughout the day, so they should be fed more frequently, however, only small quantities at a time. Small active fish like danios and newly hatched fry have higher metabolic rates and should be fed frequently, especially when kept at warmer temperatures. Water temperature regulates fishes’ metabolisms and influences how often and how much they need to be fed.

When To Feed

In nature, most fish feed in the early morning and at dusk. Exceptions are herbivores and omnivores that forage throughout the day, and nocturnal species. Although aquarium fish can be fed at any time of day, morning and evening feedings are best. They quickly learn when “feeding time” is, eagerly swimming back and forth at the surface or emerging from hiding places in anticipation of their next meal.

Make sure the aquarium light has been on for at least 30 minutes before the morning feeding and leave it on for at least 30 minutes after the evening feeding. Nocturnal species such as knifefish, catfish and certain plecostomus can be fed sinking foods shortly after the aquarium light is turned off at night.

Signs of Overfeeding Fish

The term “overfeeding” means feeding more food than your fish need or want to eat in one feeding. Even hobbyists who only feed once a day or every other day can be guilty of overfeeding if the food is not completely consumed in less than 2 or 3 minutes. Here are some tell-tale signs of overfeeding:

- Uneaten food remains in the aquarium after 5 minutes, but the fish show no interest in it. In extreme cases, a fuzzy or cottony white fungus may begin to grow on the bottom or on decorations and plants after a day or two.

- Aquarium water is cloudy or hazy and has a foul odor to it. Foam or froth may be present on the surface.

- Filter media becomes clogged in a matter of days after cleaning.

- Excessive algae growth. Even with proper filtration and water changes, nitrate and phosphate accumulation from heavy feeding can contribute to excessive algae growth.

- Ammonia or nitrite levels are elevated.

- Chronically high nitrates or low pH.

Providing your fish with the right diet and feeding schedule will ensure growth, disease resistance, vibrant colors, and long, healthy lives.

Algae Prevention and Control

Every aquarist encounters algae growth no matter how diligent you are about maintaining your aquarium. While its appearance is usually not welcome, algae is nature’s way of purifying water and removing pollutants, and it performs a valuable function in the aquarium. Some algae growth in a mature aquarium is normal, however, excessive algae can be a result of problems in water quality and maintenance habits. There are many causes for algae growth and just as many remedies. Understanding what causes algae growth is essential to preventing and controlling it.

Nutrients

Algae are aquatic plants in their most basic form, and like all plants, they need water, light, and nutrients to grow. In the aquarium, the primary nutrients are nitrate and phosphate, which typically come from fish waste but can also be present in tap water. A build-up can be caused by generous feeding, infrequent water changes or filter maintenance, overcrowding, using tap water that has high nutrient levels, or a combination of one or more of the above. If you start to see excessive algae growth, test your aquarium and tap water for nitrate and phosphate. Nitrate (NO3) should be below 10 ppm and phosphate (PO4) should be below 0.5 ppm.

To keep nitrate and phosphate levels in your aquarium low, avoid having too many fish, feed sparingly and perform regular water changes using nitrate and phosphate free water. To lower high nutrient levels and maintain optimum water quality, clean your filter regularly, use Aqueon Water Treatment Filter Pads, Kent Marine Nitrogen Sponge, Phosphate Sponge, Organic Adsorption Resin, Power-Phos or Reef Carbon. If your tap water has high nutrient levels, use reverse osmosis or deionized water with Aqueon Water Renewal, R/O Right or Liquid R/O Right when doing water changes.

Excessive Light

Many people believe that the sole cause of nuisance algae is too much light. While it is certainly a contributing factor, algae are more common in aquariums with high nutrient levels, especially if there are no live plants. Avoid placing an aquarium where it will receive direct sunlight, even if it’s only for a few hours a day. Limit the number of hours the aquarium light is on, especially if you do not keep live plants. A maximum of 6 to 8 hours of light is sufficient in unplanted aquariums, while planted aquariums should receive 12 hours of high-quality light. Use a timer to provide a consistent photoperiod.

Quality of light is another contributing factor to algae growth. Fluorescent lamps weaken and undergo a change in spectrum called “color shift” as they get older. Since algae are more tolerant of marginal conditions, they tend to prosper under gradually deteriorating light whereas many aquarium plants do not. For the best results, fluorescent light bulbs should be changed every 10 to 12 months.

Types of Algae

Brown Algae – most brown algae are a form of diatom. They are often seen in newly set up aquariums and will usually die off on their own after the tank cycles. Diatoms use silicates to build their cell walls, so if your tap water contains high silicate levels, use reverse osmosis or deionized water when setting up your aquarium. Place Organic Adsorption Resin or Reef Carbon in your filter to remove nutrients and introduce plecostomus, otocinclus or nerite snails to control brown algae in established aquariums.

Green Algae – there are many types of green algae. Some are soft and easy to remove, while others are hard and can be more tenacious. They grow on the aquarium glass as well as decorations and even the gravel. Snails and algae eating fish help keep many forms of green algae in check. Maintain low nutrients and avoid overfeeding or overstocking your aquarium to prevent outbreaks.

Blue-green Algae – these appear as a heavy, dark green film or “slime”. They are actually not algae, but rather a form of cyanobacteria. Left unchecked, they can suffocate live plants and even cause harm to fish. Blue-green algae can be removed by siphoning them from the aquarium, but they often quickly return. Several products are available for eliminating blue-green algae that are safe to use in fresh or saltwater aquariums.

Filamentous Algae – there are many forms of filamentous algae, including hair, string, beard, black brush and thread algae. They are usually caused by a build-up of phosphate in the water and can be seen clinging to plants and other decorations. Longer forms can be removed by twirling them around a toothbrush. Siamese algae eaters, mollies, redtail and rainbow sharks, goldfish and Amano shrimp are known to eat them. Shorter varieties can be eradicated using bristlenose and clown plecostomus, otocinclus, nerite snails and dwarf freshwater shrimp. Plant leaves that become covered in filamentous algae should be trimmed out. To prevent filamentous algae outbreaks, feed sparingly, do frequent partial water changes using phosphate-free water and use Phosphate Sponge or Organic Adsorption Resin in your filter.

Green Water Blooms – these suspended algae cause the water to turn bright green and very cloudy. Green water blooms are usually caused by high nitrate and phosphate levels, along with excessive light. Many hobbyists try to solve the problem by doing water changes, but the effects are temporary, and the problem quickly returns, often with a vengeance due to the addition of nutrients from tap water. Blacking out the aquarium for several days by covering it with a blanket and turning off the light can be effective, but this is detrimental to live plants and may result in ammonia and nitrite spikes when the bloom suddenly dies off. Diatom filters and UV sterilizers are the most effective cure. Chemical algaecides and coagulants also work, but again, sudden algae die-offs can spike ammonia and nitrite levels and some coagulants interfere with the fishes’ gills.

Live Plants

You may have noticed that well-planted aquariums rarely have any algae. That’s because aquatic plants remove nutrients from the water and starve out algae. Live plants are one of the most effective ways of preventing algae growth in an aquarium, but it takes more than just one or two to be effective. Live plants work best at preventing algae when the aquarium is heavily planted. Fast growing bunch plants like Hornwort, Wisteria and Rotala are very effective at using nutrients and keeping algae at bay.

Algae Eating Fish

Sometimes, despite our best efforts, some algae growth is inevitable. Plecostomus, otocinclus, farlowella, Siamese algae eaters, hill stream loaches and some freshwater sharks feed directly on algae. Bottom feeders like Corydoras catfish and other loach species help reduce nutrient build-up in the water by cleaning up uneaten food and consuming dead plant debris and other organic material that accumulates on the bottom of the aquarium. Use caution when adding plecostomus to planted aquariums, as some species are known to eat broadleaf plants like Amazon swords and Anubias.

Snails

Aquarists often think of snails as a nuisance, largely because of outbreaks of Malaysian trumpet snails (Melanoides tuberculata) and Ramshorn snails (Planorbarius spp). However, several types of freshwater snails are excellent at algae control and will not overrun the aquarium.

Mystery or Inca snails (Pomacea spp.) feed directly on algae, food and dead plant material that contribute to nutrient build-up. They are available with black or golden bodies and several shell colors. They will not eat live plants or overrun your aquarium. In fact, they must leave the water to reproduce, often depositing egg clusters on the underside of the aquarium lid. Due to their size, mystery snails are best kept in medium to large size aquariums.

Nerite snails (Neritina spp.) have gained in popularity due to their appetite for algae and beautiful shell patterns. There are many types, including some saltwater species, but Tiger and Zebra Nerites are the most stunning and best suited for freshwater aquariums. A secure cover is required as these snails are known to climb out of the aquarium. They are ideal for aquariums 20 gallons or smaller, although they can be placed in any size aquarium.

Rabbit snails (Tylomenia spp.) are a recent addition to the aquarium trade from Sulawesi, Indonesia, that are rapidly gaining in popularity due to their active nature, interesting appearance and bright colors. They do best on a sand substrate and prefer temperatures between 80® and 84® F and a pH above 7.5. As with all aquatic snails, a calcium supplement will help maintain healthy shells. They are voracious algae eaters and have very low reproductive rates, so they won’t overpopulate your aquarium. They are not known to eat live plants; however, some anecdotal accounts suggest they may be attracted to Java Ferns.

Dwarf Freshwater Shrimp

Caridina and Neocaridina shrimp are popular aquarium inhabitants that are often used to control hair and string algae, especially in planted aquariums. While most species are best suited to small aquariums, Amano shrimp (Caridina multidentata) can be kept in most community aquariums. Because of their small size, most dwarf freshwater shrimp should not be kept with larger fish species.

Filtration

Diatom filters and UV sterilizers are very effective at solving green water blooms, but not other forms of algae. Diatom filters trap suspended algae cells on a layer of diatomaceous earth. The filter should be checked and re-charged frequently at first as it will clog quickly. UV sterilizers kill the algae as they pass through the light chamber, and do not require any cleaning. Partial water changes should be done every few days to prevent ammonia and nitrite build-up. Both filters should be left on the aquarium for 7 to 10 days to ensure all algae cells have been removed.

Chemicals for Algae Problems

Chemical algaecides should never be your first choice when dealing with algae problems, as they do not address the cause of most outbreaks. They can provide a temporary solution, but sooner or later the problem will return if the original cause is not addressed. Proper filter maintenance, regular water changes, appropriate lighting and sensible stocking and feeding practices are far more effective at preventing and controlling algae growth. That said, sometimes outbreaks occur that do not respond to natural methods of preventing or eradicating them. In those instances, products like Aqueon Algae Remover can help but they should always be used as a last resort. Always follow product directions and remove carbon and other chemical media from your filter before using algae control chemicals.

Fish Compatibility

Choosing fish that get along is a challenge every aquarist faces. While there are certain combinations we know with relative certainty do or do not work in most instances, there are countless others that can go either way depending on a variety of factors. Here are some things to keep in mind when purchasing fish for your aquarium that can help determine fish compatibility.

Aquarium Size

Most fish need space, and the more they have the better they tend to get along. When fish are crowded they become more agitated and are more likely to quarrel with tank mates. A general rule of thumb for stocking a fish tank is one inch of adult size fish per net gallon of aquarium capacity, but territorial fish need even more space. Remember that the fish you buy will probably grow, and a 30 gallon aquarium doesn’t actually hold 30 gallons of water when you factor in internal dimensions, gravel and decorations. Also, what to us is a large aquarium (200+ gallons), is still just a fraction of the space fish have in their natural habitats.

Aquarium Dimension

Another consideration is the dimensions of your new aquarium. Different fish prefer different shapes and swimming spaces. Wider aquariums give active fish, like danios and barbs, the space to spread out, which in turn helps them get along better. On the other hand, tall, narrow aquariums are appealing to look at and fit into narrow spaces but don’t offer fish as much swimming space or territory as a wider aquarium. These aquariums should be used for less active fish like discus, angelfish and gouramis.

Decorations and Plants

Aquarium decorations help with fish compatibility in several ways. Most fish need a place to call their own and they define their personal areas by physical boundaries. In addition, when they can’t see each other, they tend to mind their own business. Rocks, caves, driftwood and other decorations help define territories for cichlids and other territorial fish, while tall bushy plants provide habitat and give schooling fish like tetras, barbs, danios and rasboras their own areas to occupy. When introducing new cichlids to existing populations, add a few new rocks or other decorations and rearrange existing décor to eliminate territories controlled by established fish.

Species/Origin of the Fish

Fish communicate in a variety of ways, but sometimes their signals can be misinterpreted because fish from different parts of the world “speak different languages”. Research fish before buying and try to stock your aquarium with fish from the same region, especially if they are aggressive or territorial species.

Cichlids, certain species of sharks, loaches, knife fish, mormyrids and other territorial fish do not share space well with members of their own kind or closely related species. Large aquariums with plenty of cover help, but many of these fish are best kept individually and tank mates should not be similar looking or closely related.

Asking your local retailer about how to build a community fish tank, featuring a variety of species is always a good option. Finding an appropriate fish compatible with bettas, for example, can be challenging but your local expert can help advise you as needed.

Fish Age

Juvenile fish are usually easy going, even if they are known to become aggressive as adults. They can often be mixed with a wider selection of tank mates, which they’ll accept as they grow and mature. There are many reports of Oscars and other large predatory fish coexisting with feeder goldfish that they could easily swallow, but don’t, because both fish were purchased when they were the same size, before the predator grew larger and learned to eat other fish.

Fish Size

An old aquarium adage states “if a fish can fit into another fish’s mouth, chances are it will end up there.” Most fish are opportunistic when it comes to food, and even relatively peaceful fish will try to eat other fish if they think they can. Always purchase fish that are roughly the same size as those in your aquarium. When mixing territorial fish, newcomers should be at least the same size as the largest or most aggressive fish already in the tank.

Fish Gender

Male fish tend to be more territorial and aggressive, particularly when mating. This is especially true for cichlids. Avoid having more than one male of the same or closely related cichlid species or other territorial species, especially if females are present. Keep livebearers in ratios of 2 to 3 females per male to diffuse the persistent mating behavior of males.

Number of Fish

Boisterous fish like tiger barbs and even certain species of tetras and danios are often better behaved when in large schools. Shy schooling fish are less likely to be picked on when kept in larger numbers as well. Always buy schooling fish in groups of 6 or more. While most fish get along better when they have more space, African Rift Lake Cichlids do best when crowded a little as this deters dominant fish from singling out weaker or submissive fish.

Territory & Dominance Hierarchies

These are especially common in cichlid communities, where distinct pecking orders exist. Smaller or submissive fish that are harassed may need to be removed. Removing the aggressor is another option, however, the next fish on the totem pole may quickly assume the dominant role, continuing the cycle. When adding new fish, make sure the aquarium is large enough and has enough cover to accommodate newcomers. Always purchase fish that are at least as large as the biggest or most aggressive fish in your aquarium.

Predatory Fish

We often think of predatory fish as large, aggressive creatures, typically in the Family Cichlidae. But there are other types of predators, such as catfish, halfbeaks, leaf fish, needlefish, bichirs, certain gobies, arowanas, stingrays and gar, to name just a few. For these fish, whatever they think they can fit in their mouth is fair game. It doesn’t make them mean or aggressive, it just means they’re hungry and following the law of nature. Many catfish species are nocturnal and come out at night to hunt small fish resting on the bottom.

Fish That Are Breeding

All fish that practice parental care – mostly, but not restricted to, cichlids – become especially defensive at breeding time. They will take over and control large areas of the aquarium, pushing all other inhabitants into a far corner. Anyone who has had a normally peaceful pair of angelfish spawn in their aquarium can attest to this. Be prepared to move “prospective parents” to a dedicated breeding tank.

Fish Personalities